The UNCTAD Review of Maritime Transport has been launched, with its usual wealth of data and analysis. Where do we start?

1) Distance matters

While drafting the text, using data from Clarksons Research, we had initially used the term "historical" for the long distances travelled by ships. But then we reworded, because we don't really know. Our data only goes back to the 1980s; perhaps (?) in the 1970s with a closed Suez canal some commodities had to travel even longer distances. Still, as far as data is available, we can confidently say that dry and liquid bulk cargoes go longer distances than at any time on record.

Consequence of the war in Ukraine, grain importers now have to source their grain from further away, and oil exports from Russian Federation go longer distances to new markets in India and China.

For shipping, this is good news, as it creates additional ton-mile demand. For prices, consumers, and CO2 emissions, this is bad news.

2) Emissions per ton-mile improve, but the total just keeps going up

While we all agree that emissions should be going down, the opposite is happening. Whether we like it or not, in early 2023, total GHG emissions from international shipping are 20% higher than a decade ago. The main underlying cause lies in growing trade volumes, going over longer distances (see above). Additional volatility comes from changing voyage speeds, partly in response to changes in bunker fuel prices.

Whether the glass is half full or half empty depends on whether you look at total emissions, or emissions per transport work. Taking the latter gives us a more positive picture (the glass is half full).

Unfortunately (back to the glass half empty), already in last year's RMT, building on data from Marine Benchmark, we had shown that about half of that improvement is not due to technological advances, but economies of scale.

3) Ups and downs: the costs of container shipping

We are almost back to where we were pre-covid. But not quite. There are some fundamentals that suggest (to me) that the average costs of shipping will remain higher in the next decades than in the years pre-covid.

Contract freight rates in container shipping tend to lag behind spot rates. While spot rates already went down from their historical peaks in early 2022, contract rates in 2022 remained above previous years' levels on most routes. Thanks to data provided by Transporeon, we do not only have freight rates from China, but for a matrix of inter-regional connections.

Among the intra-regional connections, African shippers paid the most in previous years, but in 2022 the highest intra-regional contract rates were intra-South America.

The rate from Asia to South America increased almost 5-fold between 2019 (pre-covid) and 2022. Thinner and longer routes tend to be more volatile, reflecting a high elasticity to changes in supply and demand, and seeing also frequent shifts in trade imbalances.

4) Congestion, and what to do about it

On average, over the years, developing countries' ports tend to be slower in their operations than developed countries' ports. There are exceptions, and in both groups there are big variations, but on average better infrastructure and more advanced technology have helped reduce turnaround times in developed countries more than in developing countries. Except during Covid. In some months in 2022 congestion was worse in North America and Europe, leading to higher average waiting times in the developed countries.

All those who confuse correlation and causality will eventually die. Still, I think there is some causality going from the implementation of specific trade facilitation solutions towards shorter vessel and cargo waiting times in ports.

Countries that have implemented the WTO TFA measures on electronic payment, risk management, authorized economic operators, and border agency cooperation also shower better indices in container port performance as per the S&P World Bank container port performance indices.

5) Demand and supply - of a legal framework

Without an adequate legal framework, the e-Bill of Lading did not advance. And without advances in the e-Bill of Lading, there was for many years apparently not enough demand for a legal framework.

This seems to have changed during Covid. Carriers are moving ahead with their electronic solutions, and governments respond with advances in the relevant legal frameworks.

6) To order or not to order new ships

Compared to existing fleet, today's order book is small. While in some markets (containers) there has been a surge of new orders, looking at the long-term global picture, I see a real danger that ship owners, yards, and banks, are all waiting for more clarity about carbon prices and the regulatory framework (and technological developments in alternative fuels) before new orders are placed.

If there is one thing we have learned from the supply chain crisis in the last few years it is that a shortage of effective supply capacity can lead to high surges in freight rates. I am afraid we may see more of this in the future if ships go slower, over longer distances, and are taken to shipyards for retrofitting. And if on top of this not enough new capacity is ordered, the steep supply curve will lead to more situations of surging freight rates in the next decades.

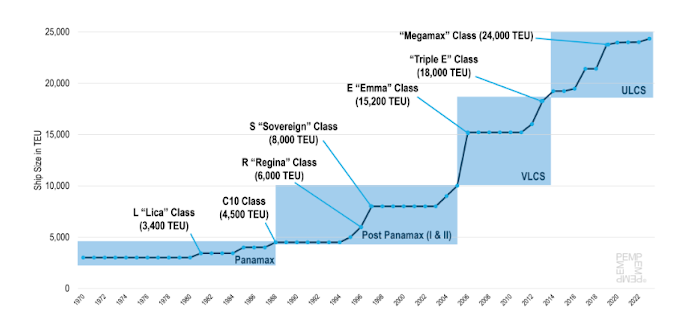

7) How much bigger?

Have we (finally, or at least for the foreseeable future) reached the max vessel size?

For decades we had seen two trends, two sides of the same coin: Ships got bigger, and the number of companies offering services to/ from the average country went down.

For the last three years, maximum container ship sizes have not increased further. And, based on data from MDST, since one year ago, we also see that the number of carriers per country has gone up.

There are ships on the drawing board with 28 000 TEU, but beyond that, I think, we may really have reached this maximum now, as the current largest container ships are comparable to the largest bulkers and tankers. Ship yard capacity, canals, and ports, but also insurance and operations suggest that this time, yes, we may have reached a maximum.

As regards companies per country, the recent surge may be temporary, following new players entering profitable markets, especially in Asia. Shippers and competition authorities will still want to keep a keen eye on developments of market consolidation.

0 Comentários